In a nutshell, when you trade CFDs, you only need to predict whether the underlying asset's price will go up or down and place your trade accordingly. However, there is much more to it. Let's start with the basics.

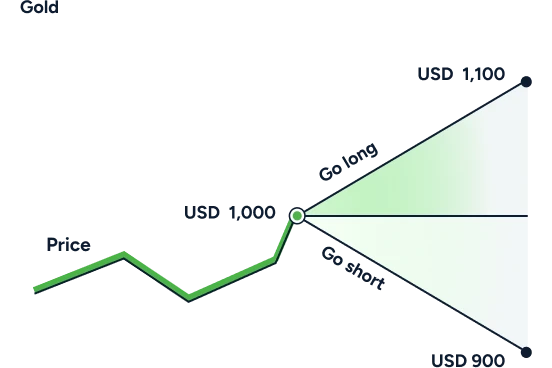

Here is an example. You've been monitoring the price of gold, and you identified some trading opportunities.

If you think the price of gold will go up, you open a buy trade, also called going long. If you think the price will go down, you place a sell trade, also called going short.

Now let’s see both scenarios in detail.

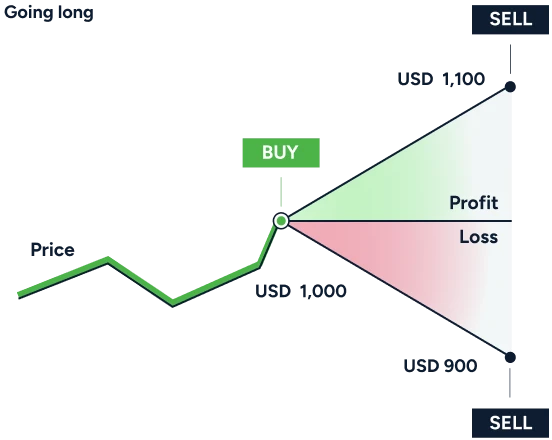

Going long when trading CFDs (buy order)

You think the price is going to go up and place a buy order. To keep the example simple, let's say the price you open your trade at or your entry point is USD 1,000. Your prediction turns out to be correct, the price does rise to USD 1,100, and you decide to close your trade (sell it).

The difference between the opening and closing prices (entry and exit points) – USD 100 – is your profit.

If your prediction was incorrect and the price went down to USD 900 instead, you would lose USD 100.

Going long in CFD trading is very similar to investing in shares. You buy a share at a certain price and sell it later at a higher price, gaining profit.

The same logic applies to a CFD contract:

Buy low (USD 1,000) + sell high (USD 1,100) = profit (USD 100)

However, if the shares you bought dropped in value instead of increasing in price, you sell them at a loss. Same with CFDs:

Buy high (USD 1,000) + sell low (USD 900) = loss (USD 100)

Just like with shares, you can hold CFDs indefinitely once you buy them. However, unlike shares, CFD positions have an extra fee for holding them overnight.

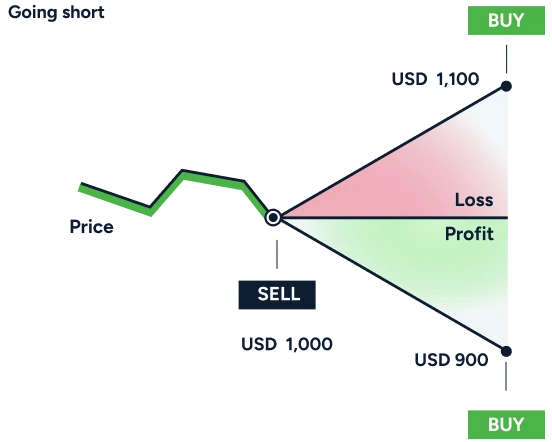

Going short when trading CFDs (sell order)

You think the price of the gold is going to go down and place a sell order. Your entry point is USD 1,000. Your prediction turns out to be correct, the price does drop to USD 900, and you close your trade with a buy order.

The difference between the buy and sell price – USD 100 – is your profit. If your prediction was incorrect and the price went up to USD 1,100 instead, you would lose USD 100.

Sell high (USD 1,000) + buy low (USD 900) = profit (USD 100)

Sell low (USD 1,000) + buy high (USD 1,100) = loss (USD 100)

The concept of shorting an instrument usually confuses novice traders because selling something you don't have seems counterintuitive. However, it's a popular practice even in investing. To short a share in investment terms, you would have to borrow it from your broker, sell it on the market and then buy it back, hopefully at a lower price.

In CFD trading, you don't actually buy or sell the underlying asset – you simply predict its future price direction. Although the trades you place are called 'buy' and 'sell' depending on your prediction, in both cases, you are just buying a contract for difference – an agreement to exchange the price difference. So, when you go long, you buy a 'buy' CFD, and if you go short, you buy a 'sell' CFD.

What is leverage in CFD trading?

In everyday life, leverage means an extra influence over something. For example, you want to lift a heavy box. Lifting it with your bare hands would be pretty challenging, especially if it's large. To make it easier, you could use a lever – a stick, for example. By pushing a stick down, you'd be able to lift a box with much less effort. That means using leverage. Understanding how it works requires some knowledge of physics, but we are not going down that route – there is no doubt it works.

In trading, the concept of leverage is no different. If you want to open a CFD trade on gold worth USD 1,000, but you only have USD 5 in your trading account, you need to use leverage.

Think of a trade as a heavy box you are trying to lift. You can't lift it with your bare hands – USD 10 in our example, so you need some leverage over it. So, what serves as a lever in CFD trading? The answer is borrowed funds. Let's see how it works.

How does leverage work in CFD trading?

Leverage in CFD trading means using borrowed from CFD broker funds to open a larger trade. Leverage is usually described as a ratio – 500:1, 200:1 or 30:1, for example. The number indicates the fraction of a trade you need to cover with your own funds to open a leveraged trade – 1/500th, 1/200th or 1/30th. In other words, it indicates how many times bigger your trade is going to be. Leverage is usually set by a broker and differs depending on the instrument you trade.

Following our example, to open a USD 1,000 trade with USD 333.33, you’ll need to use a 30:1 leverage (5 X 333.33 = 1,000). In this case, your broker covers the USD 666.66 for you.

This process is usually described as borrowing. However, just as you don't buy or sell the underlying asset when you trade CFDs, you also don't physically borrow funds. They are just automatically allocated to your account on a trading platform when you choose to trade with leverage.

Having much greater market exposure with less capital is the main attraction of trading with leverage.

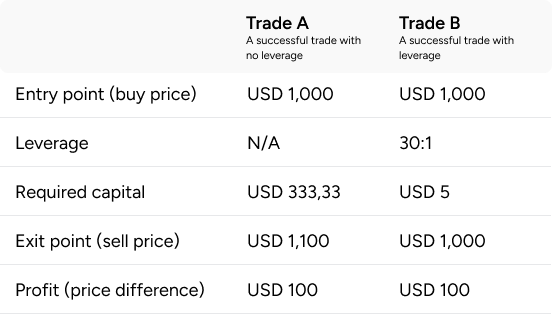

Here is a comparison of how a trade with no leverage compares to a leveraged one, assuming identical market conditions:

Trading scenarios regular trade vs CFD trade

As you can see, in both scenarios, the profit is USD 100, but with the leveraged trade, you had to pay only USD 5 instead of USD 1000 to get it.

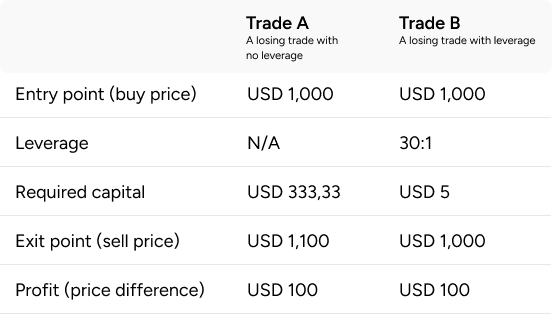

However, it is crucial to understand that leverage exposes you to much greater risks as well. In a losing trade, your loss would be much bigger than your starting capital:

Trading scenarios regular trade vs CFD trade

In a trade with no leverage, you would lose 1/10th of your starting capital – USD 100 out of USD 1,000. In a leveraged trade, you would lose twenty times more than your trading capital – USD 100 vs USD 5.

That's why using risk management tools that help you minimise the risk you are exposed to is crucial in CFD trading. In our next article, Risk management tools in CFD trading, we’ll go over stop loss and take profit and explain how they work.